Gala’s hands are hurting. He had been pounding the rock in his hand against the little rock on the ground for a long time to get the basic shape right, and now he is using another rock for the fine details. He will need the spear tip to be sharp if he wants to catch an antelope. His grandfather told him that, when he was young, the fields around the lake were covered in grass, and antelopes, giraffes, and elephants could be found everywhere. Now, the summer rains hardly ever make it here anymore. There is only sand and stone beyond the lake. This brought all the animals together, but it also means that other groups of people, who had previously lived elsewhere, came to the lake to hunt as well. Each year, there are fewer animals left. Finally, with the spear tip being sharp and tied to a stick, he goes out in search of antelopes. When he finds a group, he stalks them until he is within throwing distance. Slowly, he aims, and then uses all his force to throw the spear at the startled antelopes. Unfortunately, he misses, and the spear disappears in the lake.

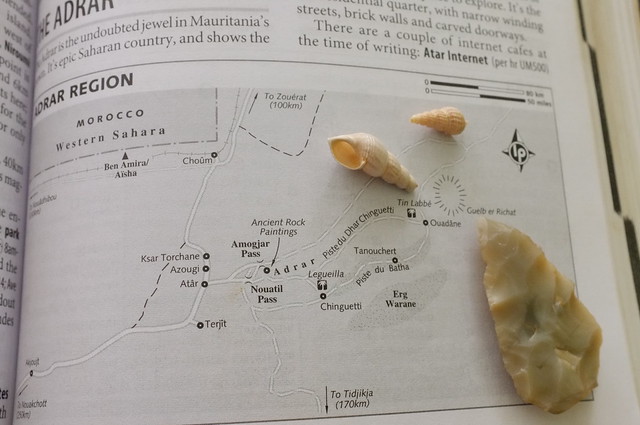

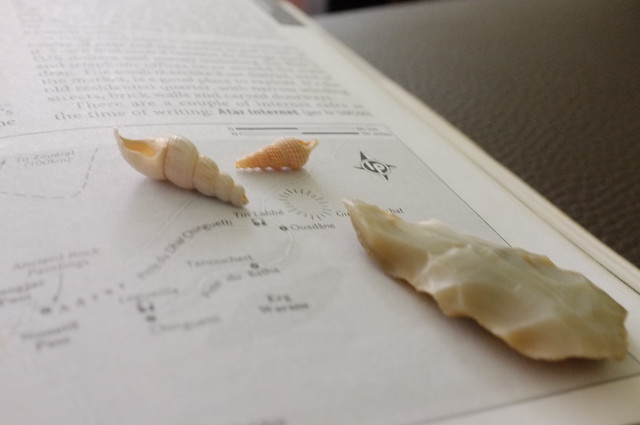

In the long run, it is irrelevant. In the decades that follow Gala’s hunt, even the lake dries out. After thousands of years as a savannah with lakes and rivers, a slight change in planet Earth’s tilt means it only takes about a century to change all of Northern Africa into a desert. The animals disappear, and so do the people; some may make it to an oasis, others die of hunger, thirst or violence. Gala’s spear tip is no longer on the bottom of the lake, but on the ground of the Guelb er Richat; an eroded circular depression that’s 40 kilometers in diameter. There it would lie undisturbed for around 5,000 years, until an woman with an interest in archeology and paleontology picks it up on one of her visits to the “Eye of the Sahara”, as the circular depression is called now that humans have gone to space and noticed the peculiar shape. The woman’s name is Cora, and she holds on to the spear tip she found until she says goodbye to a Dutch guest at her auberge, not far from the Guelb er Richat. As the guest leaves she gives him the spear tip as a souvenir, making him very happy indeed.

That’s how I imagine the history of my most treasured souvenir from my entire journey. Since the Guelb er Richat depression was a lake for several thousand years during the stone age, there are thousands of spear tips on the ground. Even though it’s not particularly rare or valuable, I will treasure Cora’s gift nonetheless; her gesture truly touched me, and I find it an incredible thought that someone (at least) 5,000 years ago spent hours working on the spear tip that I now hold in my hands, and then used it to hunt for food. After saying goodbye to Cora and Justus, I leave Auberge Bab Sahara and try to find a minibus to take me from Atar to Nouakchott, Mauritania’s capital. I will need copies of my passport to give to the police and soldiers at checkpoints, but making these copies without getting ripped off proves to be a challenge. Thankfully, the minibus which will take me to Nouakchott is reasonably comfortable. It’s from the early 90’s and doesn’t have airconditioning,

but for once I don’t get squeezed into a space suitable for a 5-year-old. The trip is uneventful; the only things breaking up our progress are a few quick stops to let people in our out at the tiny villages we pass through, and the obligatory stop at the afternoon prayer time. All in all, it’s about 440 kilometers of relatively smooth pavement taking us through the desert. After we leave the Adrar mountains, we see some dunes stretched out by the constant Northeastern wind, sometimes 10 kilometers or more in length. There are also some fields of bleached-white, almost translucent grass; in the rainy season, this part of the desert must be teeming with goat and camel herds. About an hour before we reach Nouakchott, a group of women get in the minibus. They offer everyone bottles of camel milk. Justus at Bab Sahara told me that camel milk can be consumed by people with lactose intolerance and can be held unrefridgerated for quite some time, so I happily accept a bottle.

At the outskirts of Nouackhott, we reach the minibus garage, and it’s time to find a taxi. Unlike the Adrar region, where there’s usually only one taxi per day going wherever you need to go, it only takes me a few seconds standing by the street to find a taxi. It’s a beat-up old car with nowhere to fix my seatbelt, but the driver is happy and chatty. He’s from Senegal, and is eager to point out all the “landmarks” in Nouakchott. For the most part, this is a thoroughly uninspiring city; it was a fisherman’s village of only a few hundred people until the 1950’s, when Mauritania became independent. Since it had always tagged along as the most neglected colony within the colossal French West Africa, it had never needed a capital, or much of anything approaching a center of organisation. So when the country became independent, it needed a new capital, and fast. Someone, somewhere decided that the little fishing village of Nouakchott, or “windy place”, should become the capital. In the following five decades, and especially during the massive droughts of the 70’s and 80’s, the city grew from a few hundred people, to over a million – more than a third

of the country’s population. Such rapid and mostly unplanned growth was never going to be pretty, and it shows; while there are more paved streets than in the country’s second city, Nouadhibou (which has an equally charming meaning: “place of the jackals”), it’s just as random, poor, and ugly. So the landmarks pointed out by my Senegalese taxi driver are of the category “this concrete building houses the election committee”, and “that concrete building is the national TV studio”. I briefly wonder what he’s smoking to be finding all these “landmarks” more worthy of his attention than the traffic (he leaves all other cars just enough room to avoid him as he brutally cuts them off), but he provides me the answer himself: ‘ganja man, Bob Marley Colombia!’, he says, as he pulls a plastic bag of hashish out of the dashboard. Lovely. Thankfully my hotel is just around the corner – and what a corner it is; the most ghastly fountain dominates the roundabout, with four chrome dolphins spraying water while being illuminated by blinking neon lights changing colour every few seconds. Only in Africa (one would hope) does this count as a useful way of spending public money…

Thankfully the hotel – creatively named Auberge du Sahara – is fairly decent. I get a rooftop tent for the equivalent of a little over 10 euros per night. Unfortunately, either Justus was wrong about the amount of time camel milk can be held unrefridgerated, or the people on the minibus simply gave everyone camel milk past its due date – let’s just say that I spent some of my evening on the toilet. Afterwards, I try to find a restaurant

with Western food, in order to not upset my stomach any further. After some time, I find a street catering to expats and rich Mauritanians driving blingmobiles (Porsche Cayenne et cetera). It even has a small supermarket (the first I’ve seen since Dakhla in Western Sahara) where I do some groceries, and I have dinner at a Lebanese / Sushi / Pizza restaurant – and as everyone knows, the more different specialties in one restaurant, the better, right?